“I don’t need money. I’ve got my family. That makes me happy. That’s my richness.”

[Bus door and bell noises]

No two days on buses are the same. Every day is different.

I like being a bus driver. It teaches me a lot of things. How to be sympathetic to people and have a bit of empathy. I treat everyone the same. [+]

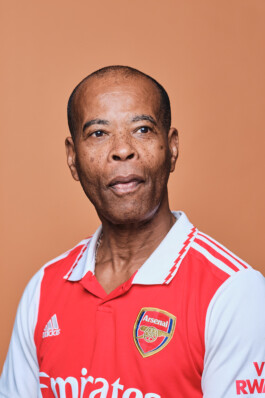

My name is Rawle Phillips, I was born in Barbados in December 1955. That was the year of the greatest hurricane that ever hit Barbados, a hurricane called Janet, which devastated Barbados in September. But I was safely in my mum’s tummy at the time.

My dad came here to work on the buses. Back in the 60s, they had a shortage of labour I guess, in this country, you know. I thought it was the British government that paid for people from Barbados to come to London to work. But I done some research and I found out that it was actually the Barbados government that loaned people like my dad their fare to come to London to work. And once they started, they would pay back that fare to the Barbados government. And that’s what happened, that’s how my dad came to this country.

I think he started off as a conductor and then went on to bus driving. That was one of the reasons I become a bus driver. I followed my dad’s footsteps, basically.

I grew up with my mum for some time. And then with my grandmother, after my mum immigrated to the UK. The house that I lived in, in Barbados was, like, a chattel house. It’s like a wooden house. Then my mum and dad used to send funds back. The chattel house become like a wall house eventually. They’ll build a block today and, and then next year, I don’t know, a bit more. Et cetera, et cetera. Until eventually they have a fully fledged bungalow.

I basically lived with my grandmother until I was 15. Then she passed away. And then, December ‘71, myself and my brother came to London. And I was age 15.

And this is my grandfather. I remember crying on the plane leaving Barbados to come to London, like, you know what I mean. After my, this is after grandmother passed away, my mom wanted to send for me.

Coming from the warmth to the cold, it was like, I couldn’t understand. In the winter times at three o’clock in the afternoon or three-thirty in the afternoon this pitch black outside, like, you know what I mean. Catching buses and sitting in the cold or walking in the cold, fingers used to be like burning, toes burning.

After a few years I settled in and I got used to it. I didn’t think about Barbados no more.

I done my schooling in Barbados but I didn’t finish school in Barbados. And when I came to London, I was too old to go to school. So I went straight to work the following year.

I was a rubber stamp-maker making rubber stamps. And embossing. I was doing a 44-hour week for eight pounds.

Every Friday, the boss would come round and give you a tobacco tin. And you open it and take out your handwritten payslip. And you probably took about seven pounds or six pounds fifty out of that eight pounds because you paid tax and insurance.

I was working with like, English guys. I’ve mixed with all different cultures. Because of the sort of person I am, I was able to mix and make friends easy like, you know what I mean. I get on with everybody.

Lunchtime, going to the pub and having some alcohol and then going back to work. That was the culture back in the day. You can’t do that now.

I’ve got nine kids, eight grandkids, and four great-grandkids. I get great pleasure from having my family around me. I sit back and I’m quite proud. This is my tribe. I don’t need money. I just got my family and that makes me happy, that makes me proud. That’s my, my richness.

Every time I travel to the Caribbean or wherever, with my Barbados passport, I find that when I’m coming back to London the immigration officers was, it was like dread, basically. Because obviously you’re being asked all these questions. ‘What was the purpose of visit to Barbados? How long are you staying in England?’ Et cetera, et cetera.

But I would say well, obviously, ‘I live here, I work here.’ Like, you know. And you would face like torrid questions, like. And there was times where, I came back from Barbados and, asked you questions, then take you to a little room. Sat me there, leave me there.

They didn’t want to encourage me to come back.

But eventually I always got through all those questions and got my stamp and in the clear.

My mum and dad went back to Barbados in 2005. But my dad, my dad passed away in 2017. I went back, obviously went back there for his funeral.

I came back second of December. Got back to Gatwick. The immigration officer asked me a few questions. Put a stamp in my passport. Hands it to me. I walked away and I took the train from Gatwick. When I got the Dalston Junction, put my passport out my pocket and flicked through it.

I saw the stamp. I thought it was just an ordinary stamp. But the stamp said, ‘Six months’ leave to remain’. Then said, ‘No employment. Not allowed to work. Not allowed to claim any funds from the public purse.’

I thought, ‘That’s not right.’ And then I thought, ‘Oh, what am I going to do? Not going to be able to go on holiday. Not going to able to go on holiday again. And I might even get sent back.’

And then, April of 2018, I was watching the news on TV and I see what they was talking about the Windrush generation. And the government have started this hostile environment to stop people from coming or to get rid of who was here illegally, blah blah blah. But the Windrush generation wasn’t illegal. When I saw that news on the television, there was the telephone number to phone the Home Office at Croydon. I rang it, I got an appointment.

They interviewed me. Then they took my fingerprints, took a picture. They made me another appointment to come back and see them. Within like three days, I had my naturalisation certificate come through the post. This whole burden I had on my shoulder just lifted.

My daughter, Shenika, she worked with me as a bus driver. We both pass each other on the road going opposite directions. I felt quite proud that she would work with me, bus driving. Yeah.