“The only way in which we can achieve anything, is if we work together.”

I was actually born right here in Kensington and Chelsea. My mother, who came to England in the mid-50s, she was already pregnant with me. Hence the reason why I was born here.

I was born in October and the first winter just did not suit her at all. So she said, ‘You know what? I’m going to send the baby – ie, me – back home to my parents.’ [+]

I came to the end of my school years in a primary school in Trinidad and then I came back to England. Now my parents brought all their children back to England because my grandparents were basically too old and, in fact, my grandmother died at that point. And we’ve been living in Notting Hill ever since. And that was in the late 60s. And I became a barrister in 1978.

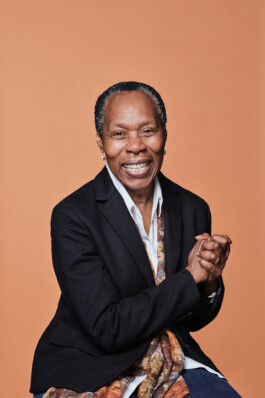

My name is Dr Claire Holder. I was the chairman and chief executive of the Notting Hill Carnival. Because I was a lawyer before getting involved with Notting Hill Carnival and I am now a senior crown prosecutor.

I remember when I was a teenager and we were being given career advice as to what to do. I knew I wanted to become a lawyer because those were my aspirations from back home. But the people in this country, the teachers at school, they weren’t quite as, as say, your parents would be, you know.

One of them said, ‘Oh, you want to be a lawyer. It’s a very difficult profession, you know. Are you sure you’re up to it?’

I said, ‘Well, there’s no question of whether I’m sure or not. That is what I want to become. That’s what my family wants me to become. So why are you questioning? Support it!’

The headmistress very bluntly said to my mother, ‘Claire is not the sort of child I would recommend for university.’

And I was not. I left school without a career plan, without anywhere to go, and someone suggested to me, apply directly to the Inns of Court.

And I was just at home one day and a letter came through the door. It said, ‘Two students have dropped out of the course at the College of Law, would you like to start on Monday?’ Well of course I, I did. Laughs.

It was so remarkable and my mother would say, ‘It’s because I prayed. I prayed, because prayer helps you to achieve everything.’

I went to a place called the Black People’s Information Centre. It was a great and innovative centre at the time where Black lawyers, Black activists, Black workers would gather and do serious work in the community. Especially around education and the sort of exclusion of Black boys from school and the sort of discipline that used to be meted out. We would have to go and represent them. There were issues around housing. And of course the major, major issue, police. So it was really worthwhile work.

And from the Black People’s Information Centre I became very well known in the community as wanting to become involved in campaigns. And I was asked to become involved in the Notting Hill Carnival. And that was in 1989, whereby the local authorities got together and decided that the Carnival had to stop.

And so in 1989, I was asked to do a response to a report that castigated the Black community and basically called us incompetent, in terms of how we manage our own affairs. And I wrote a response and the response was critical of the authorities, but also self-critical, critical of us as a community. Because I do think that while we are able to try and fend off criticism of what we do, we must be self-critical at the same time.

And once I delivered the report, people immediately voted for me to be chairman of the Notting Hill Carnival, and that’s how I became involved.

I spent 13 years with the Notting Hill Carnival, working hard, helping to stabilise it, and helping to lift standards. Its growth was organic, but at a very rapid pace. Because when I first realized there was a Carnival in Notting Hill, which was in the 70s, I was a teenager. And my brother came home and said, ‘Do you know there’s a Carnival going on? Let’s do something. Let’s be part of it.’ So in 1973 in fact, that was my first journey into Carnival.

There were literally about what, 5,000 people who were mainly Trinidadians. And nobody could understand all these strange Trinidadians who just come and jump up and wind up to pan music, ‘That don’t even make sense, you can’t even hear it.’ But nevertheless we were happy.

And then the sound system guys, who were mainly Jamaicans and who were only playing reggae music would, we consider, be a nuisance on Carnival Day because they drowned out the sound of the acoustic steelband, so you couldn’t hear them. And the sound music, the reggae music, encouraged you to dance in a static way rather than move on the streets. And so there was a great resentment between the two communities.

But then Leslie Palmer, round about 1975, invited the sound systems to officially participate in the Carnival. Let’s accommodate. And the numbers attending carnival just mushroomed.

So they too came into that celebration of our right to be here, our right to be there, our right to commemorate and celebrate our ancestors. And that’s how my journey and my understanding of what Carnival should be. Us coming together. Whether you are Jamaican, Grenadian, Nigerian, Ghanaian, it is about our togetherness as Black people.

And when I was voted in as chairman of Carnival in 1989, I didn’t find that togetherness. There was so much hostility still, with Trinidadians saying, ‘If you, Jamaicans, want to be involved in Carnival, go and do your Carnival elsewhere.’ And, ‘Why should Grenadians be in charge of Carnival? They shouldn’t be on the Carnival committee. They don’t know nothing about Carnival.’

I, we as Trinidadians you know, you subscribe to that, because as far as we concerned, ‘We’re the only people in the world who know anything about Carnival! Because Carnival started with us and is we ting,’ and – a load of nonsense. Because you had to overcome that lack of togetherness and cohesion.

And so my journey through Carnival was mainly about building that cohesion and building a respect for the event and what it symbolises.

In the 13 years that I was at the head of Notting Hill Carnival, it was a difficult journey. It was a very difficult journey and took a lot of hard work. But you know, the end results were very good.

And then the biggest achievement we had was in 2000, when someone from Buckingham Palace called and said, ‘Her Majesty would like the Notting Hill Carnival to feature in her Golden Jubilee.’

At the same time, in coming to her attention, in coming to the attention at that level, people thought that I was a problem. They had to undermine me. That’s, jealousy sets in and it was all broken down. That in-fighting where people thought that I was pushing myself forward and they should be the ones getting all these accolades. But you know whatever accolades I got, and I got quite a few, they were for Carnival, not for me. They were for Carnival.

I had a very unfortunate parting from Carnival. In fact, I was thrown out of Carnival by people who were basically jealous of the success we were having, amidst a lot of, really, lies that could easily be disproved. And I did disprove those lies and I took them to court, and won.

My values are built from what I experienced in the Caribbean, and what we hold so dear to us. You know, Carnival in Trinidad is a national event. There’s an Act of Parliament to preserve Carnival because the people of Trinidad and Tobago understand, that is the event on which the nation was founded. That is the event which represents the values that the enslaved fought for and won, having sacrificed many millions of Africans.

And I look here and I see other communities who commemorate their sacrifices. And I want the same sort of reverence be paid to our ancestors. And Carnival is the event which we can develop and do that commemoration so that they would have something to look up to and respect.